In the first of a three part series, Jon Naunton, co-author of Business Result and Oil and Gas 2 in the Oxford English for Careers series, shares his most challenging experience as a teacher: teaching English to beginner students in Libya.

In the first of a three part series, Jon Naunton, co-author of Business Result and Oil and Gas 2 in the Oxford English for Careers series, shares his most challenging experience as a teacher: teaching English to beginner students in Libya.

If asked to name the most challenging thing I have done as a teacher I would probably say that it was teaching the Roman script, handwriting and basic English spelling to absolute beginners during my time in Libya. While most of us have taught beginners (usually not real beginners) at some point in our teaching careers, real out-and-out adult beginners are a rarer breed. Teaching students who have no notion of the Roman script also adds a further challenge.

Nearly all our students were males between 18 and 45. Many worked in the souk (market), and a few even had problems reading Arabic. Many fell by the wayside after a couple of courses, but those who persevered have my unswerving and unconditional admiration. They came to school three times a week for a one hour lesson. Most never missed a session. Their sheer enthusiasm and commitment was infectious and motivating for anyone who came into contact with them.

So how did our school go about teaching these students? I make no claims to the programme, as it had been devised over a number of years by previous teachers and directors of studies, notably Sue and Jeff Mohamed and Jane Alexander. Drawing on their experience of teaching primary children, their knowledge of Arabic and the demands of a beginner’s structurally graded syllabus, they created a methodology that was a cocktail of different elements. I would not claim that this methodology had all the answers, but it certainly provided an excellent point of departure and impressive results.

As you know, Arabic is written from right to left; English from left to right. I seem to remember we had a macabre, two frame flashcard showing the link between smoking and cancer to make this point! The first task was to teach the alphabet. And the first question was whether to teach the letter at it sounds in the alphabet, or as it sounds in words. We could teach ‘a’ as / æ / in ‘cat’, but unfortunately that notion does not take us very far as ‘a’ has three different sounds in ‘banana’ and takes on its full alphabetic value in ‘cake’. Our policy, then, was to teach letters as they sounded in the alphabet and deal with how letters sounded in words as we went along.

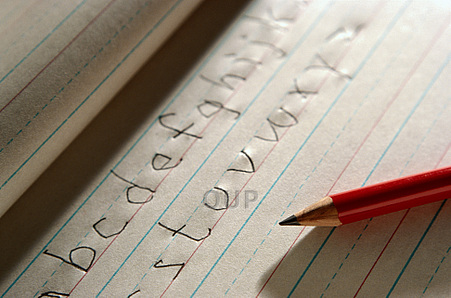

The next issue was the order in which the letters should be taught. Do you go ‘a, b, c, etc’ or group them differently? At our school we decided to group them by similarities in shape, so ‘m’, ‘n’ and ‘h’ were grouped together, ‘a’, ‘d’ and ‘g’ formed another group and so on. Clearly, it is important that students grasp the relative height and size of letters from the start. For this reason we used special exercise books that as well as the main line had faint lines above and below so that the ascenders (e.g. ‘t’) and the descenders (e.g. ‘g’) could be shown. This lined paper was also valuable to show the relative heights and shapes of capital letters and numbers. We marked up our chalk blackboards in a similar way.

The teacher would painstakingly present each letter by saying its name as she wrote it slowly on the board. Great care was taken to show the direction that the letter took. Afterwards the students were told to write several lines of the letter in question, saying the letter each time they formed it. This long, remorseless work required concentration and tenacity on the part of the student. The teacher went round the class checking that students were forming the letter correctly and respecting the direction.

Another issue was the difference between printed characters and handwritten characters. Cursive (joined-up) writing presents the further difficulty of knowing where one letter ends and the other begins. So we had to choose which script to stick with – obviously different teachers could not have the luxury of writing letters differently from their colleagues. We used a variant of ‘Marion Richardson’, a script which was and may still be extensively used for teaching young children how to write.

Have you ever had to teach Roman script to absolute beginners? How did you go about it? What advice would you give to a new teacher of beginners?

I encountered a similar experience teaching ESL to Chinese students in California. Chinese and English not only have different visual representations but also have different mental coding. Chinese speakers rely on visual representations whereas native English speakers rely on phonological representations. Each Chinese character represents a entire concept or thought whereas each letter of the alphabet in isolation has no meaning whatsoever. Considering this, and the way in which the Chinese learn their own language, I decided that the best approach was to teach the whole word in visually presented material. I found that Chinese students could better recall a word once they saw it visually represented than phonologically presented.This alters all known methods of second language acquisition in which the spoken word (listening and understanding) comes first and is of primary importance. It was as well striking to see how the motion of the Chinese script system of lifting the hand for each stroke was transferred to Roman script making it look at first sight illegible, somehow resembling Chinese characters although at a closer look the letters where quite readable. Evidently the hardest part for the students was to bridge years of hand training in their own language.

Thank you for this incredibly valuable insight!

[…] If you missed it, read Jon’s first post about The Alphabet. […]

[…] If you missed it, read Jon’s first post about teaching The Alphabet. […]

[…] you missed them, read Jon’s previous posts about teaching The Alphabet and […]

[…] Teaching English as a Foreign Script – Part 1: The Alphabet … So we had to choose which script to stick with – obviously different teachers could not have the luxury of writing letters differently from their colleagues. We used a variant of 'Marion Richardson', a script which was and may still …https://teachingenglishwithoxford.oup.com20 .. […]

[…] Teaching English as a Foreign Script – Part 1: The Alphabet … Teaching English as a Foreign Script – Part 1: The Alphabet. Published 20 … Our policy, then, was to teach letters as they sounded in the alphabet and deal with how letters sounded in words as we went along. The next issue …https://teachingenglishwithoxford.oup.com20 .. […]

Wow, it must have been seriously challenging to teach Roman script to Arabic speakers. I taught Roman letters to Korean students for a few years, and I encountered a few problems.

One was the way that Roman letters can have so many different sounds in English, for example “C”. To explain the difference in the pronunciation of “C” in words like cat, race, cheese etc. was pretty tricky. Even though there are some rules, the number of exceptions caused a big headache for my students.

Another was that Koreans are not used to having upper and lower case letters. So they would often mix upper and lower case letters in a sentence, meaning tHey WRotE liKE ThiS.

A final problem for me and for my students was that they had formed habits of writing Roman letters unclearly, for example making “h” look like “n” when handwritten. This of course causes problems when reading something they have written, for example “Egypt nas not weatner” instead of “Egypt has hot weather”.

Anyway it is a major challenge. Interesting blog post, thanks.

I get pleasure from, result in I found just what I used to be having

a look for. You have ended my four day lengthy hunt!

God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

[…] The Alphabet […]