Robin Walker is a freelance language teacher, teacher educator and materials writer. In this post, he considers the vital role that English now plays in World business and communication, and discusses the increasing importance of English as a Lingua Franca. Robin hosted a Webinar “Pronunciation for International Intelligibility”. Watch the recording of this webinar here.

Last month I took on two clients, both seeking coaching in pronunciation. Pablo works in the finance department of a US multinational that has a key European plant here in northern Spain. His boss is Irish, but most of the people he uses English with are non-native speakers. Pablo handles accounts for the whole of Europe, and even within the confines of his office, he’s in daily contact with speakers from over 17 different countries.

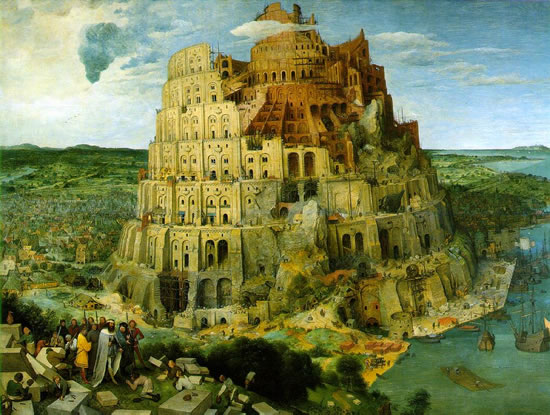

Ana works at the Spanish branch of a German company that makes air bridges, the metal and glass tubes that feed us on and off planes in airports around the world. She uses her English for telephone calls, Skyping and video-conferencing, and with Chinese, Brazilian, Arabian and European clients. English dominates her daily life despite working in Spain, and her office is a Tower of Babel in the making.

Image courtesy of fimoculous on flickr

Wow! It’s happened. (They said it would.)

Wow! It’s happening right now. (It’s everywhere I go.)

And wow! It’s going to go on happening far into the future.

English has gone global, and is being used much more today as a lingua franca (between non-native speakers), than as a native language (between native speakers), or as a foreign language (between native speakers and non-native speakers).

So what? The world speaks English because the native speakers taught it to them. Keep teaching them native English and they’ll be OK.

But will they be OK? Are native speaker norms the best thing when non-native speakers are communicating through English? Well, not for some. Not, for example, for two Japanese translators at the 2009 Davos World Economic Forum. For them, the non-native speakers were far more intelligible than the native speakers.

And when Chantal Hemmi checked this out in her research in Tokyo, she got the same results. Of five regular competent users of English for international communication (presidents, prime ministers and CEOs), it was British Prime Minister David Cameron who was considered the least intelligible (Hemmi, C. 2010. Perceptions of intelligibility in global Englishes used in a formal context. Speak Out! 43: 13–15).

Image courtesy of worldeconomicforum on flickr

As David Graddol explains in his British Council report on where English is heading:

In organisations where English has become the corporate language, meetings sometimes go smoothly when no native speakers are present. Globally, the same kind of thing may be happening on a larger scale.

This is not just because non-native speakers are intimidated by the presence of a native speaker. Increasingly, the problem may be that few native speakers belong to the community of practice which is developing amongst lingua franca users.

(Graddol, D. 2006. English Next. Why global English may mean the end of English as a foreign language. 2006. London: British Council.)

English is a native language for some and a foreign language for others. But most of all today, English is a lingua franca. And for this brave new world, the beautiful old English might not do.

I think effective communication has always been the goal, not necessarily being ‘correct’. Too many times students can learn ‘the rules’ perfectly and not be able to produce a comprehensible discourse or text.

Nice article, Robin. Thanks. You won’t be surprised that I have a couple of comments. 😉

1. You say that English “is being used much more today as a lingua franca (between non-native speakers), than as a native language (between native speakers), or as a foreign language (between native speakers and non-native speakers).” How do we know this? I have never seen any reliable figures.

Simply counting the number of people who are NS or NNS doesn’t, in itself, tell us who communicates more in total. That is also a question of the intensity of use, which is generally higher I would guess among NS (of any language). Neither, in my view, do the world tourism figures in David Graddol’s “English Next” prove this point: for example, a Spanish person travelling to Cuba or Argentina would count as a NNS-NNS combination, although English is unlikely to be the main language used.

Of course, in a way, this is an academic issue because there is no doubt that English is widely used in NNS-NNS interactions, which is the key point. But I still think we should be careful about such sweeping statements.

2. Rather than emphasizing the distinction — false in my view — between NS (bad international communicators) and NNS (good international communicators), we should be trying to increase the communicative skills of both groups (which in most cases aren’t good enough, whether NS or NNS). And this involves not just linguistic skills.

Actually, I agree with both your points Ian. We need to factor out from the international arrivals data both cases like travel between Spanish-speaking countries, and also travel to see friends and familes ‘back home’. It would be good if someone had the time and patience to do that, but I wanted the graphic to show the general scale of the issue.

Second, I am a great believer in language awareness work with NSs including cross/inter cultural communication skills.

Robin: thanks for the reference to Chantal Hemmi.

Sorry to be slow getting back to you, Ian, but this week is a double public holiday in Spain, and I’ve only just got back to the land of email & internet, etc.

Apologies also for the sweeping statement. I’ve been told off about this before! But although the figures you ask for aren’t available, I think that David Graddol’s data on tourism movements does actually provide a good broad view of the state of things. And then contact with professionals like Pablo & Ana (false names obviously to protect their identity, but very real people), plus our own observations as we travel around the world – these things constantly bring home to me how much English is now being used as a lingua franca.

I also agree with you that NSs are not per se bad international communicators, but there is the assumption that as a NS you are automatically intelligible, and this is not so. Again, it would be great to have statistics, but in their absence I’d love to have a euro for each time students have lamented the ‘fly-in-the-ointment’ effect of some native speakers in a discussion. This is what I’m referring to, of course, when I quote David Graddol.

In my opinion, as an English teacher, the qualitiative aspect of the produced language should not be undermined. If it’s only a question of being intelligible then language schools, learning centres and private tutors have no purpose whatsoever any more since the Internet is full of language learning possibilities and one can always translate their business text in Google Translate and thus make it highly intelligible to another peer.

We should as teachers, on the contrary, make efforts in providing pur students, colleagues etc with the so-called correct knowledge of English not to mention the correct contextual meaning of vocabulary. If we do this the most people would produce intelligible text and be understood better and everyone will be happier since they know the language they produce is quality and they may feel confident in using it correctly.

Now, of course, there are people who just want to get their job done no matter how well or not but it has been my experience that people, especially business leaders and subordinates, wish to have a correct, complete and understandable knowledge of English since we live in a multicultural world and we cannot separate language from culture. We wouldn’t like that done to our own language and culture or would we?!

Teaching people to be intelligible is no easy matter, John, and taking an ELF approach to intelligibility would certainly not put private language schools and other learning centres out of business. Quite the opposite, in fact. Nor will we solve the issue of communication through Google translate, which with relatively simple work between two very well understood languages like Spanish and English, regularly fails to come up with a correct translation.

And yes, we obviously do want to give our learners correct English. But ‘correct’ is not an absolute. Correct US spelling or pronunciation is not alway correct for UK English. Something similar happens with Australian and New Zealand Englishes. US ‘to think out of the box’ is ‘to think out of the square’ in Australia, for example. Correct, then, is related to speech communities and their norms. In ELF situations these norms will frequently be the same as the norms of native-speaker communities, but not always.

In your Oxford Seminar, you said teaching intonation in terms of the rise and fall of pitch was not possible. But I’ve read a studies that indicate teaching intonation and other supraegmentals actually affect more change more quickly than teaching segmentals. Though this was not in a lingua franca context, it seemed to indicate to me intonation can be taught (pitch)- and I have had students make significant progress in this. For my students who are not using English as a lingua franca, teaching intonation is very important to their careers, as without the native pattern, they come across sometimes as uncaring, disinterested, or generally conveying a meaning interpreted by native speakers that they do not intend. By focusing on their pitch patterns, they transform how they come across in business, and this makes a big difference for their working relationships. This makes me very curious about your statement in the seminar. Can you give guidance to research behind the comments you made, as I would be interested in reading them.

Hi Angela

Yes, this is an interesting area. Firstly, you are spot on when you differentiate between ELF and the context your own learners are using English in. I think we all agree that NSs are very sensitive to what is often referred to as the attitudinal function of English. Just last week I got a reply from a dive operator in the Canary Islands, a NNS of English, that felt curt and unwelcoming to me. I dived with the centre for two days despite this first contact, and he turned out to be a really nice guy. What I’m trying to say is that for learners who are going to use their English predominantly with NSs, there’s an issue here, and one that as teachers, we will need to address.

The problem begins when you try to address the use of pitch movement (tone) in NS English. I recommend you read Peter Roach (English Phonetics and Phonology, 4th edition, CUP, 2009). He sums the whole situation up on pp150-152, when he says that “of the rules and generalisations that could be made about conveying attitudes through intonation, those which are not actually wrong are likely to be too trivial to be worth learning. I have witnessed many occasions when foreigners have unintentionally caused misunderstanding or even offence in speaking to a native English speaker, but can remember only a few occasions when this could be attributed to ‘using the wrong intonation”.

He then goes on to suggest that the “attitudinal use of intonation is something that is best acquired through talking with and listening to English speakers”, i.e. that it is learnable through exposure, but not teachable in the classroom. This is what I was trying to get at in the webinar, and if I had learners who dealt predominantly with NSs, as you do, I’d try to guide their exposure to this attitudinal use of intonation through analysis of films, or of recordings of the sort of meetings they attend. This guided exposure would increase their sensitivity to this NS use of tone, and hopefully this would reduce the time needed for them to acquire competence in the system.

When we come to ELF contexts, the situation is different. Jenkins, for example, is quite clear about choice of tone in ELF : “Even if it were possible to teach pitch in the classroom, I do not believe that the use of ‘native speaker’ pitch movements matters very much for intelligibility in interactions among NBESs. This feature of the intonation system seldom leads to communication problems in the ILT data and, on the rare occasion that it does so, it is accompanied by another linguistic error … … Nuclear stress, however, is a completely different story.” (Jenkins 2000: 153).

In genral, we need to teach to the norms that will operate in the speech communities where our learners will use their English. For the EFL situation you describe, Angela, you’ll need to give your learners as much help as is possible with the tone system of English. For ELF interactions, the NS use of tone is very largely irrelevant.

Best

Robin

Robin, thanks a lot for the webinar. I have been teaching English phonetics (as a separate subject) to English majors in a Ukrainian university for the past four years and I thought I knew a lot about teaching pronunciation. However, you cast a completely different light on that matter, which was very helpful. It was also delighted to hear some of my major beliefs (not necessarily the popular beliefs in ELT nowadays) confirmed.

In your webinar you talked about a book or an article that dealt with teaching English pronunciation to speakers of Russian. Could you give a reference to that article please? Thank you!

I’m glad the webinar was of use, Liliana. But you’re being modest, I think – if you are teaching phonetics then you obviously do know a lot about pronunciation. The only thing that is different about what I said is that I was looking at how NNSs communicate successfully at the level of phonology, which is something that standard phonetics and phonology courses tend to overlook, despite its importance for the role English now plays as a lingua franca.

The reference I made to teaching English to speakers of Russian was to Chapter 5 of my own book in the OUP Handbooks for Language Teachers series (‘Teaching the Pronunciation of English as a Lingua Franca’). In this chapter experts from 10 different L1 backgrounds examine how the corresponding L1 phonology can help or hinder the learner’s attempts at gaining full competence in the Lingua Franca Core. One of the ten L1s covered is Russian. This is written by Mikhail Ordin.

Best

Robin

Hello Robin! I can’t find anywhere over the internet the webinar you are here referring to.

Is there any chance that you can help me find it?

Thanks in advance,

Julieta.