There are widely-held perceptions that numerous language schools refuse to hire non-Native English Speaker Teachers (nNESTs). In this guest article, teacher, teacher trainer, and founder of TEFL Equity Advocates, Marek Kiczkowiak, shares his thoughts on how this can have negative effects on students and teachers alike, and looks at an alternative, more egalitarian hiring model, that emphasises qualifications and experience, regardless of their mother tongue.

Dear Student,

I would like to tell you a few things about your English teachers which you might not have been aware of. As a teacher, I really care about your language progress and I would like you to understand what characteristics make certain teachers unforgettable, so that you can make an informed choice and pick the best language school.

It is very common for language schools to advertise only for and hire exclusively native speakers (NSs). I am sure that you have come across (or perhaps even studied in) institutions that boast having only native English speaker teachers (NESTs), who will teach you the ‘real’ English. In theory, this sounds fantastic. After all, who wouldn’t like to speak like a NS? In practice, however, there is a catch. Numerous non-native English speaker teachers (nNESTs), that is teachers for whom English is not their first language, have been rejected out of hand, not for lack of qualifications or poor language abilities, but simply for not being a NS.

It is very likely, then, that among those rejected nNESTs there were numerous teachers with higher qualifications and more experience than the NEST who was hired. The recruiter might have based their choice on the assumption that all nNESTs speak ‘bad’ English. While I certainly agree that language proficiency is very important for a successful teacher (I certainly wouldn’t like to be taught by somebody who doesn’t speak the language well enough), I agree with David Crystal, one of the ultimate authorities on the English language, who in this interview said that “Fluency alone is not enough. All sorts of people are fluent, but only a tiny proportion of them are sufficiently aware of the structure of the language that they know how to teach it.”

In addition, there are language tests (e.g. IELTS, TOEFL, CPE) which can be taken to prove a teacher’s proficiency. And there is no doubt that you can reach native-like level in a language – people did that even in the dim and distant past when teaching (and certainly language schools) was almost non–existent, or simply backwards by our standards. Take Joseph Conrad, for example. Born, bred and baptised in Poland as Józef Korzeniowski, he only emigrated to England in his late teens. Yet, he still managed to outwrite most of his contemporaries, introducing the English to the beauty of English.

So yes, of course, a successful teacher should be highly proficient in the language. There is no question about that. You need a good language model. However, it is a mistake to assume that only a NS can provide it, and to dismiss any nNEST out of hand.

What is more, being proficient in a language is not the only characteristic of a good teacher. For if it were, there would be no need for teaching courses and university degrees in pedagogy. Successful language teaching is so much more than merely knowing the language and I think this should be reflected in the way language schools hire their staff.

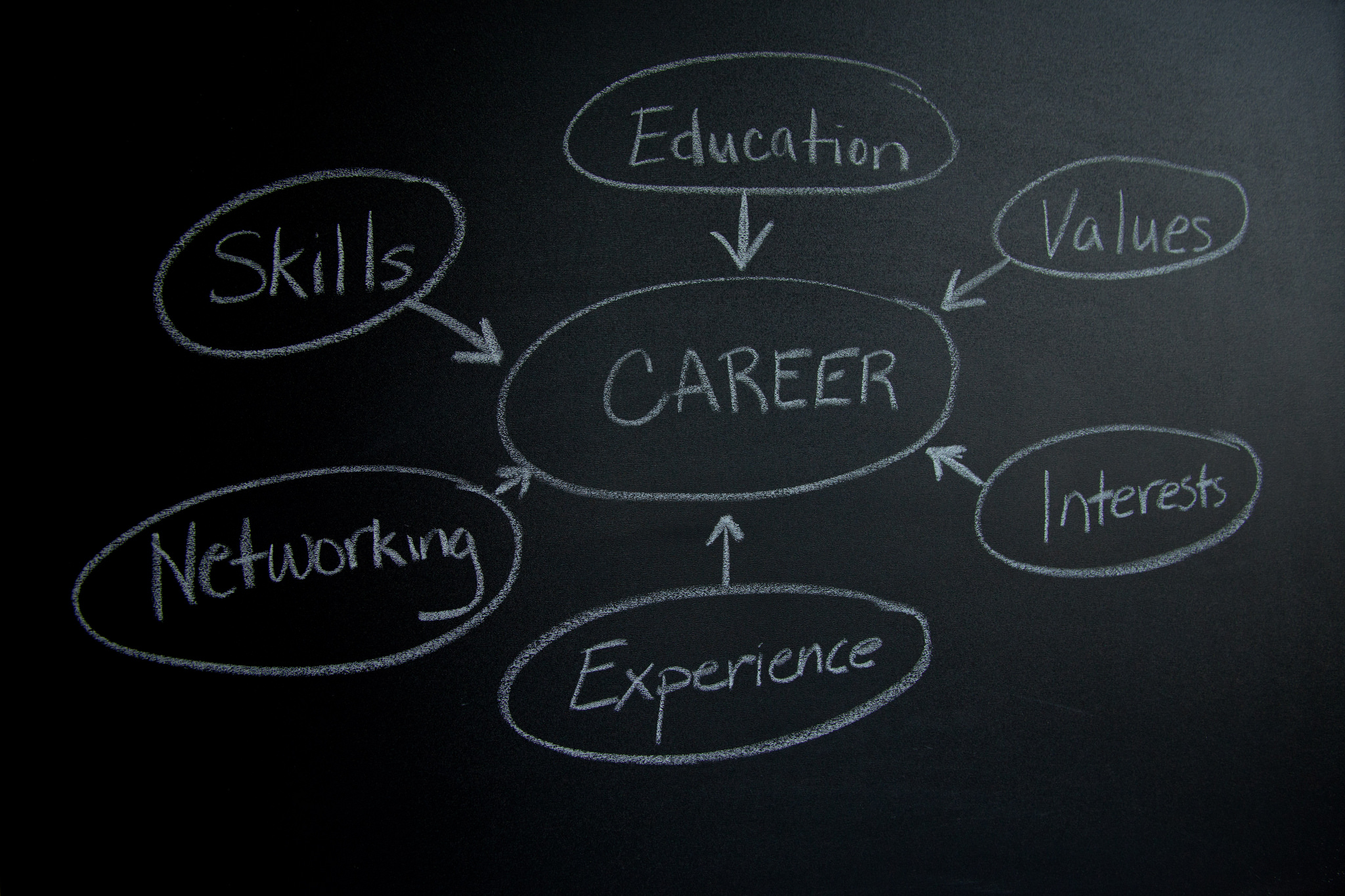

So, if as a student you want to know whether a particular school is worth investing your money and time in, ask them how they recruit teachers. On the whole, more trustworthy and renown schools select successful candidates based on logical and measurable criteria which are independent of and irrelevant to being a NS or not. For example:

- Qualifications

- Years and variety of teaching experience

- Language proficiency

- Personal traits

As a teacher, the best staff rooms I have worked in, and the best language schools with the happiest students, all have a healthy mix of NESTs and nNESTs, an opinion confirmed by many Academic Directors such as Varinder Unlu, who works for International House London. This is because the two groups can bring different characteristics into the classroom, learning from each other and improving as teachers. So while NESTs might be experts in language use, nNESTs have many important strengths which should not be overlooked.

For example, having mastered the language themselves, a nNEST can serve as an excellent learning role model. They can give you numerous tips that will help you learn faster based on their practical insights. They might also be more aware of the difficulties you are having since they have been through them too. And empathy and understanding are vital for successful teaching to take place. Many nNESTs have also studied the language on university level and can therefore bring a deep understanding of its mechanics.

I suggest then that as a client you question how your school chooses its teachers. Do not be swayed by slogans such as: We employ only NESTs because we care about your progress.

If they did, they would be employing the best teachers out there: native and non–native alike. And you have the right to receive the highest quality of education. So get involved and support equal teaching opportunities for all teachers.

Best regards,

Marek Kiczkowiak, TEFL Equity Advocates

I’m glad you addressed your letter to the student, because it is the student who decides whether a school employs a NEST or not. In Malaysia it is extremely expensive to employ a NEST so the student has to pay for it. If they want to they can go to another language centre that offers nNEST and it will be significantly cheaper.

Saying all this, I don’t rate a prospective teacher based solely on their passport though language proficiency, qualifications and experience is obviously very relevant, I base it on their professionalism and work ethic which I have to say is on the whole missing in the nNEST in this country compared to the teachers from the western world…..so for me a NEST is not just about language proficiency it’s about having the western world professional work ethic…….this is just from my 18 years of recruitment experience in this field in this country.

My experience is that the students who come to our school are promised NEST and in turn have to pay for it. Saying that we ensure that they get the best of the best, and from what I can see from our market in Malaysia, we certainly are ranked (among the students) in the top 2-3 schools in the country for this very reason – the other 2 are also NEST schools.

Just saying…shoot me down if you wish, but I am speaking the truth for this country. It’s all about business. So if you can convince students with your letter that having a non native is just as good, it will certainly be a lot easier for the business owner because their overheads will be a 3rd of what it is now…..so all the best.

Thanks for your comment.

I can certainly see your point and I understand that making profit is indeed very important for any language school. I think it is worth asking, though, why your school is ranked so highly. From what you are saying, it is not because you employ NESTs, but because you employ the best teachers out there. While many NESTs might embody the values you’re looking for in a good teacher, there will be a fair number who don’t. Equally, there may be a significant number of local or ‘western’ nNESTs who will also fit the profile.

While there is always a grain of truth in stereotypes, I don’t think it is necessarily a good way of judging applicants. If we did, all mechanics in the world would be German, and all the chefs Italian or French.

As far as students’ perceptions go, I think the industry has to a great extent shaped them. For decades in many countries the quality of local teachers was low (e.g. Poland, Spain) and the language schools have advertised NESTs as the only good solution to the students’ language problems. It became a great selling point. It is no surprise to me then that before a new generation of qualified, proficient local nNESTs appeared on the market, the students had already developed negative stereotypes.

Fortunately, many of the most respected language schools and organisations have since changed their policies and are now employing simply the best teachers, regardless of their mother tongue (e.g. the British Council, International House). Many students are also starting to see the strengths that nNESTs have, and the ones which have been exposed to good native and non-native teachers will tell you that it really doesn’t matter where the teacher is from, as long as they are proficient, knowledgeable, engaging, fun, etc.

Finally, as educators we also have a moral obligation to educate our clients. If they hold discriminatory believes, it does not mean that we should condone them. After all, if a student complained that their teacher was black (or Asian-looking, or a woman, etc.), you would not apologise and provide what they demanded, would you? Instead, you’d think the student is racist, and perhaps you might try to reason with them. The same goes for students who refuse to have classes with nNESTs when there is no pedagogical reason to complain. It’s a form of discrimination which we perhaps have not yet sensitised ourselves to.

Thank you for replying. I think your key point is employing the best teachers, and at our school we consider all the best teachers NESTs, meaning we employ a number of nNEST teachers but we consider them NESTs as they embody the western work ethic, creativity and language acquisition of a NEST.

For sure there are plenty of lazy good for nothing NESTs out there too who wouldn’t get a look in our door, so by no means am I talking about someone being better at teaching English purely because of their passport….

But trying to convince a student that a nNEST is going to be better for them than a NEST is still an upward battle, that’s why we call them all NESTs, that way they don’t even know the difference.

It is an uphill battle, but I think the perception of nNESTs has been changing among students. In my opinion, the more exposure students get to professional, qualified and experienced nNESTs, the less likely they will be to maintain their prejudices.

And I still maintain that as teachers our job is to educate our clients. The market demand doesn’t have to shape the industry. I think the industry can reshape the market demand.

If we focus on employing qualified and experienced teachers, regardless of their nationality, students will start to notice that there are good and bad teachers in both groups. Of course, there will always be a small number that will refuse to have classes with, for example a nNEST, or a black teacher, or an Asian one, for no reason but mere prejudice. However, I don’t think that number is very high, and therefore unlikely to jeopardise your business. Fr example, IH London Academic Director told me that over 4 years she’s had 4 students complain about their teacher not being a NEST. Hundreds more complained about, for example, teachers not giving any homework.

Thanks for a thought-provoking exchange 🙂

Agree. Thanks for the discussion.

Here in Finland private language schools typically employ freelance language trainers and the rates don’t differ between native and non-native speakers (that would be illegal). In the public sector nNESTs are in the majority due to the system which requires teachers to have a Masters degree in their subject (ie English in our case) and proof of their pedagogical skills.

When a language school bids for an SLA with a corporate client or a public organisation, the bidding process requires the teachers to be named with their CVs attached. This is where local teachers are sought after by language schools. Typically a nNEST will have a Masters degree in English philology which earns more points than a NEST with a Bachelors degree in whateverology and an online TEFL cert. So most private language schools in Finland have a mix of nNEST and NESTs on their books.

The Adult Education Centres (funded by the local municipalities) will invariably use nNESTs to teach beginner and intermediate groups (mostly for the reasons given by Marek in his article) and then use NESTs to teach Advanced students, ESP and conversation classes. There is a heavy dependency on published materials – coursebooks – and most of those published in Finland use Finnish instructions (eg for grammar) and invariably include translation exercises which few nNESTs would be able to manage. Many of the students who ask for NESTs are in fact hoping for a classroom culture that breaks away from traditional coursebook-focused teaching. Many expect more than language training: they want an insight into American or British culture thrown in as well!

Things are changing. Nowadays most of the classes I teach include students from many different linguistic backgrounds. English is a lingua franca in Finland (in companies, universities etc) and many foreigners moving to this country decide to improve their English language skills in parallel to learning Finnish. English is needed to do business with Russia, China and even Scandinavia and the Baltics (where Swedish was the lingua franca until the Baltic countries joined the EU). Managing a multicultural classroom is challenging and some nNESTs may not have the variety of experience from teaching internationally which many NESTs have acquired.

Finally, Marek did not specifically mention pronunciation which is a hot topic in TEFL circles. There are many advocates of the lingua franca core (LFC) who argue that NESTs are not necessarily the best voice models for teaching English as a Lingua Franca (ELF). Yet, invariably students who ask for a NEST will give pronunciation as one of the main factors for their choice. I think the jury is still out on that one.

Hi Penny,

Thanks for commenting. Very interesting to hear what the situation is like in Finland. It’s very positive I think that schools have a healthy mix of both NESTs and nNESTs. It also seems very logical how teachers in language schools are hired.

A point I’d like to make, is I can’t see why the two groups should be given different classes. It’s just another stereotype that NESTs are better at conversational classes, whereas nNESTs at teaching grammar. As an Academic Director, I’d like all my teachers to be versatile, adaptive and willing to teach whatever level or class I need them to teach. I’d also pick teachers for classes not based on whether they’re NESTs or not, but rather based on their experience. For example, I wouldn’t give a Proficiency class to a native speaker, just because they’re a native speaker. I’d give it to a teacher who’s taught such levels before and is experienced enough to handle it, or to a teacher who expressed their preference for it.

when it comes to breaking away from the course book material, it’s just another stereotype I think to say that only NESTs can do it, or are better at it. Most well-qualified nNESTs that I’ve worked it use a bit of DOGME in their daily practice. Plus, if the DoS notices that there are differences in the way the two groups teach, it could and should be addressed through teacher training. Otherwise, the gap will only become greater (not to say that one style is better than the other – best to mix both, I think).

As far as teaching pronunciation goes, while students might think they’ll somehow pick up their teacher’s accent, I’ve hardly ever seen that happen. You won’t sound like a Brit just because your teacher is British. At least the odds for it are pretty low. When I taught in Spain, for example, 99% of all students, regardless of their level and of where their teacher was from, had a Spanish accent in English anyway.

In addition, if a student demanded pronunciation classes, e.g. to speak with a particular accent, I wouldn’t necessarily give them a NEST. I might, but this would depend on whether the teacher could imitate the accent in question and has had experience teaching pronunciation. Equally, a qualified nNEST who ticked all the boxes would be a good choice. After all, the fact that you speak with a particular accent doesn’t mean that your students will pick it up, let alone that you’ll be able to teach it.

Best,

I think there are fairly obvious reasons why nNESTs are used for teaching beginner classes in Finland and you’ve already enumerated all of those. As for conversation classes, I generally refuse them as I’m not too comfortable with the concept of “teaching” conversation; but it does annoy me when Adult Education Centres will ONLY offer conversation classes to foreign teachers (ie NESTs). Up here there are very strong pre-conceived ideas (among the general public) that Finns don’t know how to do small talk so only a NEST “can” take those classes. It’s a cultural thing rather than a language issue per se.

As for pronunciation, I agree with what you say but I think you are dreaming if you believe things will change in that respect. I strongly believe that ELF pronunciation can be taught by nNESTs but most students, if given the choice, will opt for a NEST. Go figure. As a NEST who does a lot of pronunciation work, I can assure you I would never try to change a student’s accent (a Spanish accent is wonderful!) and I would certainly not expect them to try and mimic my Home Counties RP! I just help them improve their intelligibility (if it’s an issue). But occasionally I do have students with very ambitious goals in terms of pronunciation and I respect that too. If someone (eg a banker who travels frequently on business to London) wants to sound more British then that’s OK too.

I agree that it’s important for teachers to be adaptable and versatile but we tend to market our teachers as specialists in a particular field (eg I had 20 years experience in business before becoming a teacher so I get a lot of the ESP business and finance groups, BEC etc). I think that makes sense. It is also my choice not to teach beginners. And most nNESTs would not volunteer to teach a pronunciaiton class. So, for the most part, I think we are a self-selecting crew: we volunteer for classes (rather than wait to be “given” them) – we know what we like doing and our DoS is cool with that.

Overall, I have more of a problem with discrimination against NESTs whose lack of an MA in English precludes them from applying for University language teaching jobs. For example, I can (and do) teach business in English but I can’t teach Business English!

Hi Penny,

Regarding pronunciation, I totally agree. Sometimes you do get a very ambitious student with a very specific goal. I think the point I’m trying to make is that such students are very few and far between, so that not employing nNESTs because of their arguably poorer pronunciation, or inability to teach a particular accent, is – if we look at the industry as a whole – not a valid argument. The second point I was trying to make is that with such a student you really need somebody who will not only speak (or be able to imitate) the accent, but also somebody with a sufficient awareness of the phonological features in order to teach it. In this way, it is similar to ESP. You need a teacher with specific knowledge or training, regardless of their ‘nativeness’.

I think teachers choosing to a certain degree which classes or levels they would like to teach is fine (as long as they are prepared to teach something new every now and again when they have to). The point I was trying to make is that it should not be assumed that only NESTs can teach conversation classes, or that nNESTs are only good at low levels. These are stereotypes.

Finally, I don’t think it is discrimination. An MA is an achievable qualification. We might argue whether the bar has been placed too high or not, but nothing stops one from getting an MA.

Thanks for your comments!

Yes, nothing wring with asking for an MA. That wasn’t quite my point (my point was probably off topic anyway). My problem was with the local obsession that to teach English you have to have an MA in English even if you are a native speaker. So a NEST with an MA (eg in Business Administration) teaching Business English in a university gets lower pay than a nNEST with an MA in English. Many excellent NESTs that I know come from a variety of different academic backgrounds whereas almost all nNESTs in Finland have degrees in… English.

Teaching ESP in demanding subjects such as law, medicine, engineering etc is tricky for anyone with no experience in the subject area. NESTs are possibly more likely to have experience in other subject areas as well as a good level of academic English and/or general training in pedagogy.

Stereotyping nNESTs as “good at low levels” is based on factual evidence: students generally prefer nNESTs at lower levels and NESTs don’t volunteer for lower level classes (unless they have a good command of the L1). I agree it is a problem. I have to deal with “fossilised” errors in quite advanced students who confuse “he” and “she” (neutral pronouns in Finnish) and are unable to master the use of definite and indefinite articles (no articles in Finnish). Maybe it could be argued that the absence of NESTs in primary school education is partly to blame for this!!!

Anyway, I think we agree on everything. Maybe the only difference is that in Finland the NESTs seem to suffer as much from the existence of these “stereotypes” as the nNESTs do!

Thanks for the reply, Penny.

I can see your point about MAs. A bit strange, I agree.

Many NESTs do have a much more varied background, but I think it’s not worth using the stereotypes. Many NESTs might have university education, and therefore awareness of academic conventions, but there are also many that haven’t been to university.

I think its quite harsh to blame nNESTs for the fossilised errors. We both know that no matter how many times you try to hammer certain grammatical points in, sts still get them wrong. And if sts could learn how to speak correctly just by listening to correct input, then wed be all out of jobs. Simply listening to BBC or CNN would be enough to speak perfect English.

Thanks for commenting and responding 🙂

“There is a heavy dependency on published materials – coursebooks – and most of those published in Finland use Finnish instructions (eg for grammar) and invariably include translation exercises which few nNESTs would be able to manage.”

…Oops, that should be “…which few NESTs would be able to manage”.

[…] Leer este artículo del British Council sobre en qué ocasiones en conveniente un profesor de lengua extranjera hablante nativo de esa lengua (y cuando no es necesario): https://blog.britishcouncil.org/2014/07/18/is-it-always-preferable-to-employ-native-english-speaking-teachers/. Interesante. (ver también https://teachingenglishwithoxford.oup.com2014/10/14/is-it-always-preferable-to-employ-only-native-english-speakin…😉 […]

I am a nNEST and reading this all these comments make me feel both angry and and relieved. All I now is that there is discrimination both from the students and the institutions. And we, as teachers, shouldn’t encourage that. A teacher is a teacher whether he or she is from England or from Colombia. Who is better than the other is a pointless discussion and we shouldn’t go around generalizing about that or any other discriminative attitude or thought.

I am an English teacher and my first language is Spanish but I don’t teach Spanish because I can’t teach it, I am not trained for that. If I was a Spanish learner and my teacher was American or British and he or she teaches me well, and if I understand his or her explanations and I enjoy his or her classes I wouldn’t request another teacher just because his L1 is not Spanish. The fact that he is from another country is completely irrelevant as long as he or she teaches me well. By the way, I would really like to meet some a day an American or British Spanish teacher!! I am sure that Spanish learners would not discriminate them just because of that.

In addition, I have met a lot of NESTs that, quite frankly, are very bad teachers. The students notice that. In my short experience as a teacher I have had the opportunity to replace some NESTs in English institutions and in multinational companies and, as embarrassing as it is for me, many of them wouldn’t go back with their native teacher. Do you know why? Because I, we, the nNESTs, give them hope. We are the living proof of what they want, we show them that they CAN make it and that they don’t need to die and be born again in an English speaking country to talk, write, listen, and read properly and have good communication skills in English.

Regarding pronunciation, in my short experience I have noticed that, at least for Spanish speakers, NESTs fail to teach them English pronunciation and the reason is that they don’t know enough Spanish to identify which, where and why they have difficulties in pronouncing proper English. Spanish speakers cannot even hear most of the English sounds because they don’t exist in our language, therefore an adult brain is physically incapable to hear as it is. The brain hears what is more similar to what it already knows. That is why Spanish speakers have trouble pronouncing the voiced th or the v. They don’t exist, so the brain doesn’t hear a voiced th, it hears a d, which is the most similar sound in Spanish. The same happens with the v (and many other English phonemes) the brain hears it as a b. So, if the brain is not able to identify the differences when it hears a new sound, it would never be able to pronounce it no matter how much drilling, repetition or imitation you make in class. There is where you need to incorporate their L1 in order for them to start to see the differences in those kinds of sounds.

If the teacher has an accent or not, it doesn’t matter, the important thing is that he or she has good English pronunciation (it is very different to have an accent than having bad pronunciation, everyone has an accent).

Another thing that people don’t take into account is that nNESTs, just because they are nNESTs, study more and make a really big effort to teach just as well as a good NEST who is trained and has studied to teach English. We give a good example to the learners and that motivates them to keep on studying and not give up. We are learners too, but in a much more advanced stage and learners, if they want to, they can get there too. Why should people deny them that?? Or why should employers pay them less than a NEST?? It is extremely unfair, and that attitude must end whether you are in Colombia or Malasia (I didn’t know that Western civilization was ethical and Eastern not), or Poland, or Hong Kong, it doesn’t matter. Teachers should never ever be judged by their nationality and, as teachers, NESTs and nNESTs, we should repudiate that attitude both in learners and employers.

I am a nNEST in Colombia. Reading the letter and the comments made me feel both relieved and a little bit angry. As teachers, NEST or nNESTs, we should not encourage the belief that nNESTs are not good English teachers and express out loud that it is (yes, it is) discriminating and extremely unfair. If I were a NEST I wouldn’t accept a job in a place where nNESTs are not hired just because of that, or where NESTs are better payed than nNESTs. Doing that is encouraging a discriminating belief and it is, precisely, what creates that kind of discrimination, both in learners and employers.

A teacher should always be hired only based on its qualification and nationality shouldn’t even be asked. A teacher can be a good teacher whether he is from the UK or US or from Pakistan or Colombia. The same way, a teacher can be a bad teacher even if he is from UK, US, Australia, NZ… or from Saudi Arabia or Afganistan, or Peru! What’s important is that he knows how to teach what he is teaching.

There could also be many Americans or British who would like to teach Spanish (though I know none), and I am sure that they wouldn’t like to feel discriminated just because they were born in a non Spanish speaking country.

My L1 is Spanish but I don’t teach Spanish. I can’t teach Spanish! I would be a terrible Spanish teacher because I didn’t study for that, I studied English so I should have the same rights as any other person.

If we all agree that it is unfair and discriminating we should do something about it and not just say it. We should not accept jobs with that kind of policy. That is how things change. As teachers we have a lot of influence in our students, we are an example for them, so when we say something we should act accordingly. And, when NESTs don’t care or ignore such matters, I would like them to think “what if it happens to you? How would you feel if you were the one being discriminated just because of your nationality? Would it be fair that all the effort you have made all those years of studying and working and struggling to be a good teacher, you would be rejected just because your L1 is not English?”. I’m telling you! It is not very nice! nNESTs make an EXTRA effort to be good teachers, just because of the fact that English is not our L1 for us is more difficult than for a native, so we study harder, and that, itself, is a plus that should be regarded and appreciated.

I would really like to meet someday a not native Spanish teacher (or any other language)., he or she would understand how frustrating it is to live in a world where his own colleagues encourage that discrimination by working in places with that kind of policy and where he is payed less money than others just because of the place he was born.

It is so unfair that we shouldn’t even be discussing it. It simply shouldn’t be happening.

And about pronunciation and teaching lower or higher levels, I agree that we shouldn’t generalize those ideas either. A teacher is good at what he or she likes to teach. I, for instance, like teaching lower levels to adults, and pronunciation/phonetics (and I’m not native!), and, for what my students say and all the evaluations they take, I can say that I am as good as any other native teacher, sometimes even better. They learn quickly and good English with good pronunciation (one thing is to have an accent and another thing is to pronounce properly. Ex: if a student says “bery” instead of “very”, it’s not because of his accent. That is bad pronunciation no matter if the student has Spanish, or Colombian or Brazilian or French or whatever accent).

Anyway, I think I got a little bit carried away and I apologize, but this is an issue that deeply affects nNESTs in many ways, and, in the end, it also affects learners.

Finally I would like to thank all of you for your inputs and thoughts, they are very valuable (and I don’t care if you are a NEST or not, hahaha! ;D ).

.

Thanks for your comment.

I definitely agree with your main comment: teachers (and people in general) should not be judged based on stereotypes, superstitions and prejudice. Especially in a professional context when there are perfectly fair and measurable criteria to judge your ability as a prospective employee.

Regarding the point you make about teaching pronunciation, I have hinted in previous comments here that it is not about being a NEST or not. What it takes is having the knowledge and the ability to transmit it. Students won’t pick up your accent, or drop their own, because of exposure to ‘correct’ pronunciation. This has to be taught and it is certainly true that the knowledge of phonemes, both in the sts L1 and in English, is very helpful. You need to show sts how a particular sound is produced, how it differs from similar sounds in their L1 or in English. And in order to do this you need to have the knowledge. Being a native speaker is completely irrelevant.

Thanks for this thought provoking article.

I’d say the biggest problem is the short-sightedness of the system. In most adverts for EFL/TEFL/ESL/EAL/ESP teachers the recruiter asks candidates to have a CELTA or sometimes a DELTA. These are qualifications that native speakers will go for if they can’t get a job in their field after university. Non-native English teachers tend to have a Bachelors or a Masters degree in English language and literature with a teaching qualification. I’ve lost count of the number of institutions that told me they won’t employ me because I ‘only’ have a Masters in TEFL (from, shock horror, a foreign uni) and not a CELTA.

Well, at least this is the situation in the UK.

Hi J.B.

Thanks for commenting.

The short-sightedness is indeed shocking. I’d add that often a NEST with only a CELTA will be given preference over a nNEST with more experience an an MA and a CELTA.

Regarding the MA vs CELTA, I’ve always thought that having an MA in English was treated as an equivalent of the DELTA. I can perhaps see where the recruiters are coming from. The CELTA and DELTA (with all their shortcomings) are practical and well-known teaching courses. as a result, the recruiter knows ‘exactly’ what the candidate might be capable of. On the other hand, different universities have different standards and follow different programs. For example, you might do an MA in English, but not a single course on teaching methodology, let alone any involving actual practical teaching.

Of course, an MA in TEFL is a different story and I am surprised that you have been turned down because you don’t have a CELTA or a DELTA. I’d definitely prefer somebody with an MA in TEFL to somebody with a CELTA (all other things being equal).

Best,

Marek

Hello everyone,

Well, this is a very interesting article!

I work as a Language Consultant (Teacher, Teacher Trainer and Materials Writer) for the British Council in India though I ‘m not a native speaker. I hope that does prove something, doesn’t it? I mean….I couldn’t agree that you more with the idea that we don’t need to have a native tongue to be able to teach English well. Not all speakers of any language can be good teachers, can they? I think speaking a language and teaching it are two different ends of the world. Of course, assuming that Teacher A has good subject knowledge, everything else depends on how honest, efficient and professional one is in the classroom and outside. While these factors are more culture-specific, they do vary from person to person too. Therefore, the debate isn’t certainly about choosing a NEST or a non-Nest – it’s more about choosing a good or a not-so-good teacher.

Marek (if I could call you by this name) – I appreciate the line of thought in your article and commend the approach that you’ve suggested for teacher recruitment.

Regards,

Huma

Couldn’t agree more, Huma. Let’s hope more recruiters choose teachers that are good, regardless of where they’re from.

Hi Marek,

I just looked through your website and it does look interesting! I’d like to get involved!

Huma

Hi Huma,

Apologies for not getting back to you earlier.

Please use the contact section on my website to get in touch. We can chat about how you could get involved.

Best,

Marek

Reblogged this on Bluesassociazione.

I certainly agree and disagree both on this article.I think being Native speaker or being teacher of English are completely different concepts.This conversation is interesting where both concepts have shown there positive and negative sides.

Hello everyone.

I’m an English with Tesol University student in Wales, doing my dissertation on issues around NESTs and nNESTs.

A personal experience inspired me to choose this subject.

In the summer of 2015, I entered in the ‘arena’ of job search. Until then, I had read about the difficulties that non –native speakers face while looking for a job, but I couldn’t imagine that an employer would reject an exceptional applicant just because of their first language. I was looking for jobs in summer camps as an English teacher, and eventually, I managed to have an interview with one in a European Country. My interview went great, as my interviewer informed me, but the recruitment team ‘wouldn’t settle with hiring a non-native speaker, no matter how good my interview was’ as I was told by him. It was the first time that I realised in what a tough market I was entering, where skills and competence often come at the second place. Let alone, how many tabs I had to close on Tefl.com because the ads are for Native Speakers only!

After so many years of dedicating a big part of my education on the English language, I never thought that my nationality ( I’m half Greek, half Polish) would be my ‘weakness’. It’s really uplifting to see so many people fighting for nNESTs equal rights especially when these people are NESTs, who don’t just accept to be benefited by the fact that English is their L1 and see the other side of the coin.

Thanks to all these people, including Mr. Kiczkowiak, whom his name I find very often on my researches about this subject.

Hopefully more people will start to think like this over the following years.

Dzi?kujemy pan Kiczkowiak!

Hello everyone!

I’m an English with Tesol University student in Wales. I’m currently working on my dissertation, on issues around nNESTs and NESTs.

In the summer of 2015, I entered the ‘arena’ of job search. Until then, I had read about the difficulties that non –native speakers face while looking for a job, but I couldn’t imagine that an employer would reject an exceptional applicant just because of their nationality. I was looking for jobs in summer camps as an English teacher, and eventually, managed to have an interview with one in a European country. My interview went great, as my interviewer informed me, but the recruitment team ‘wouldn’t settle with hiring a non-native speaker, no matter how good my interview was’ as I was told by him. It was the first time that I realised in what a tough market I was entering, where skills and competence often come at the second place.

After so many years, dedicating a big part of my education on the English language, I never thought that my nationality (I’m half Greek, half Polish) would be my ‘weakness’. During my research for my dissertation I have read a lot of articles from people fighting for nNESTs’ equal rights on our field. It’s really uplifting to see a lot of NESTs getting involved, not just settling down and being benefited by the fact that English is their L1, but actually fight alongside nNESTs and being able to see the other side of the coin.

Thanks to all these people, including Marek Kiczkowiak, whom his name I have seen very often during my research.

Dzi?kujemy pan Kiczkowiak!

[…] read an interesting article a while back and have seen it popping up on a couple of other sites and forums […]

[…] https://teachingenglishwithoxford.oup.com2014/10/14/is-it-always-preferable-to-employ-only-native-english-speaki… […]

I want to ask a specific question with the hope of getting a response, though this is an old blog post.

I have a bachelor degree in engineering and want to join CELTA course to teach English abroad. I am not a native speaker of English Language. So, I have no idea whether I will be able to find a job. I know Russian (studied in Ukraine), Turkish (my mother tongue), and English (learned in USA during my stay that lasted 8 months). I love learning languages and teaching what I know.

I would like to know what are my chances of getting a teaching job. Any personal advice would be appreciated.