Robin Walker is a freelance teacher, teacher educator, and materials writer. He has been in ELT for over 30 years, and regularly collaborates with Oxford University Press and Trinity College London. Today he joins us to preview his upcoming webinar ‘Pronunciation Matters’, on December 6th and 7th.

Robin Walker is a freelance teacher, teacher educator, and materials writer. He has been in ELT for over 30 years, and regularly collaborates with Oxford University Press and Trinity College London. Today he joins us to preview his upcoming webinar ‘Pronunciation Matters’, on December 6th and 7th.

At first glance it would seem that it is not really possible to question the idea that pronunciation matters. How can you learn a language without learning its pronunciation? Who will understand you if your pronunciation is poor? And will you understand them? Yes, the case for teaching pronunciation seems pretty solid, but the reality in classrooms around the world is often very different. Time and time again, when I give talks and workshops on pronunciation, teachers confess to me that what I’ve said has been enlightening, but that sadly they don’t have time for pronunciation in a syllabus that is already busting at the seams. It’s logical, then, that if they are short of time something will have to give, and pronunciation is an obvious choice, especially with courses that focus more on written than on spoken English.

Teachers say they don’t have time to teach pronunciation in their syllabus.

But can we really push pronunciation out to the margins of ELT like this? Surely it does matter. The connection between pronunciation and speaking, for example, is immediately apparent to anyone who has started learning a new language. But pronunciation is also about listening; it is not enough to recognise a word in writing, because if you don’t know how it’s pronounced you won’t recognise it when listening to someone using the word. Spanish learners of English can fail to recognise the word ‘average’ even though it is spelt the same way in both languages. This is because they are expecting a four-syllable word and so fail to make sense of the correct, two-syllable pronunciation.

Pronunciation is also an issue for listening because of the way that words that are pronounced one way when said in isolation can sound quite different when they are part of a sequence. My own students kept using ‘Festival’ to start their essays. I couldn’t work out why and until they explained that it was the way I started any instructions I gave them in class. It wasn’t, of course. What I’d been saying was ‘First of all’ but because of their poor pronunciation they completely misheard what I was saying.

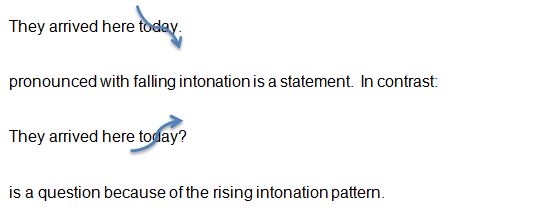

Vocabulary, too, has a pronunciation element if we want to use a new word when speaking, and there are many examples of the connection between pronunciation and grammar. A rising tone at the end of an affirmative sentence, for example, turns it into a question to the ears of the listener. Thus:

Speaking, listening, vocabulary – yes. But writing?

Less obvious, admittedly, is the link between pronunciation and writing, and it was clear to me for a long time, and to all of my colleagues, that pronunciation and reading are simply not connected. Or at least that is what I thought until I heard Michael Swan and Catherine Walter speak at the 2008 IATEFL conference in Exeter. Their session was about the problems learners face when reading in English. Poor pronunciation, Catherine explained, often lies undetected behind the poor reading skills of many students. If we want them to get better at reading, she proposed, help them to improve their pronunciation.

I listened to this concluding remark in amazement. Suddenly everything fitted into place. Pronunciation does matter. And rather than being marginal to the core elements of ELT, it lies at the very heart of teaching English. Grammar, vocabulary, speaking, listening, writing and reading – what holds them all together, what is common to them all, and what is central to ELT, is the very same pronunciation that got pushed out onto the margins some time in the mid-80s.

Pronunciation is the glue that holds everything else in teaching together.

How this is, how pronunciation operates as the glue that holds everything else in teaching English together, I’ll explain in my webinar in December. I’ll also look at goals for learners, because if the goal in the past was to sound like a native speaker, the situation today, with English being used the world over as a lingua franca, is not so simple. I’ll be looking at priorities for our learners’ pronunciation, too, because if there isn’t much time to fit everything in, we need to focus on what matters most.

So if you accept that pronunciation matters, and you want to find out more about what matters in pronunciation, join me in December, and we’ll put pronunciation in its proper place at the heart of ELT.

Show me, please, where you’ve found <> (Spanish punctuation system) to be a word in Spanish? Did you intend to write “garaje” (similar but not the same as “garage”?

Reblogged this on ELT by M Amin Gental.

Reblogged this on hungarywolf.

I’m a massive fan of pronunciation, so I think it does matter, and is important. What’s frustrating is that most students don’t seem to think they can make a difference, which puts the question on how we show them it matters…looking forward to the webinar.

Hello,Is there a cost to this?Karen CocinaMain Street Schoolhouse, Inc.

[…] For a deeper insight into Robin’s views, check out this blog on Oxford University Press title Does Pronunciation matter? You can also get links to his […]

[…] to speak with proper pronunciation to facilitate effective learning in the English Language! Read this blog entry by the Oxford University Press English Language Teaching Global […]

A language is a system and as such it needs to have every element integrated. One element out, the whole thing is out. The closer you speak to a native speaker the better chances you have to understand spoken English. A whole different thing is trying to understand or being understood by someone who is not a native speaker, that is a different matter.

“Average” has three syllables where I come from (The North).

[…] For a deeper insight into Robin’s views, check out this blog on Oxford University Press title Does Pronunciation matter? You can also get links to his […]

[…] Learning a Language Tip #4: Pronunciation Matters […]