Step Forward Series Director, Jayme Adelson-Goldstein, identifies several task types that incorporate the College and Career Readiness Standards for Adult Education (CCRS) and the English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education(ELPS) as a preview of her CCR presentation at TESOL 2017 this month.

Step Forward Series Director, Jayme Adelson-Goldstein, identifies several task types that incorporate the College and Career Readiness Standards for Adult Education (CCRS) and the English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education(ELPS) as a preview of her CCR presentation at TESOL 2017 this month.

Taking Our Instruction to Task

The focus on 21st century college and career readiness (CCR) for adult English language learners has sent adult ESOL instructors scrambling to create (or locate) rigorous lessons that

- include practice with complex text and its academic language (at the appropriate level),

- require critical thinking and problem solving, and

- provide direct instruction in language strategies.

Many of us need look no further than our texts to find the basis for meaningful tasks that help learners accomplish all the above. Task-based instruction (TBI), as discussed by N.S. Prahbu, David and Jane Willis, David Nunan, Rod Ellis and others, creates opportunities for learners to use authentic language and processes that result in a product or tangible outcome that learners first share and discuss, and then analyze in order to improve their accurate use of the language.

In the world outside our classroom, we do not use language skills in isolation. Both the College and Career Readiness Standards for Adult Education (2013) and the English Language Proficiency Standards (2016) show the intersections between skills. A well-designed task embodies this connection, creating a more robust use of language and greater relevance for the learner. In this blog, we will look at basic task design and provide three task types that integrate CCR skills.

A Basic Task Framework

Your preparation for the task includes gathering any essential task materials (e.g. links or tags for research, poster board and markers, sentence or paragraph frames for report backs, etc.) and determining what instructions are needed in addition to those in your textbook.

1) Present the task objective to the class and any essential information learners will need, (e.g. instruction vocabulary and/or background knowledge)

2) Next, show learners a model for–or example of–what they will produce (a list, a chart, a poster, a written report, a photo, etc.) including examples of the type of written work they will generate for their report on their task outcome(s). Note that the outcome of the task is not a right or wrong answer. A successful task will have divergent outcomes that take full advantage of each team’s prior knowledge, problem solving, critical thinking, creativity and language skills.

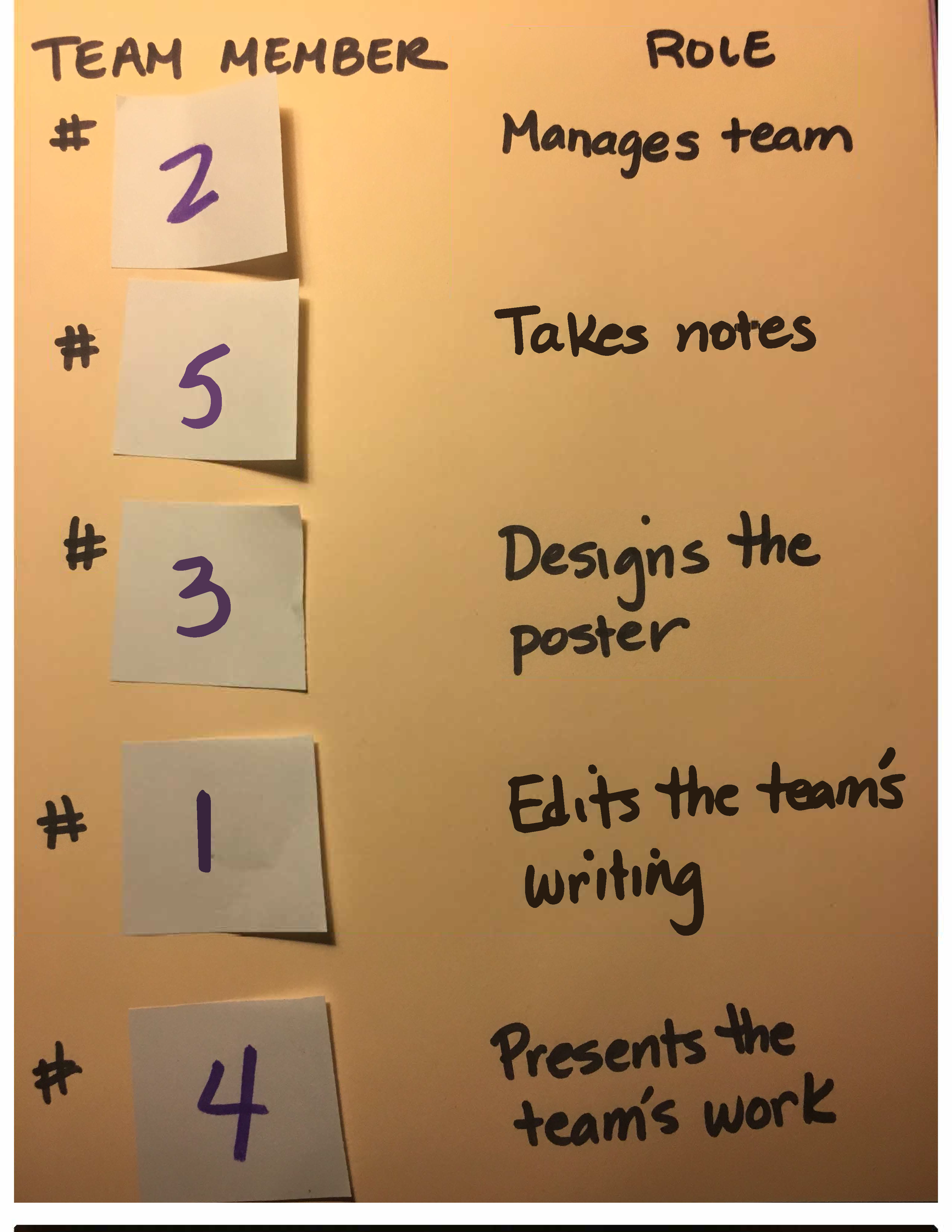

3) Learners form pairs or teams and select (or are assigned) team roles. Task instructions are distributed to each pair or team or posted/projected for all learners to see. General comprehension is checked and time limits are set.

4) While learners work on the task, you are an observer and monitor. Once they complete it, they plan and rehearse a short report back on the work they did and their outcome(s), (e.g., the list, poster, conversation, advice letter, etc.). At this point in the process, you engage with the teams, supporting learners’ language needs as questions arise.

5) When it’s time for teams to report out, they can take turns presenting to the whole class or make simultaneous reports, with one or two members of each team traveling to other teams to make their presentation.

6) Briefly highlight each team’s success following their presentation or once all presentations are complete. Ask the class to provide feedback as well.

7) Once all presentations are complete, it’s time to help learners notice global and/or egregious errors that interfered with their collaboration or their report out. Provide practice or take home activities that correlate to the language challenges learners had during the task.

Developing a Task Repertoire

A task repertoire can make instructional planning much easier, but there are some important considerations. First, there is the issue of teacher intention versus learner interpretation (B. Kumaravadivelu, 1991) We can address this issue with

1) a learning objective or outcome that is written at the learners’ level and is accompanied by an example of the outcome;

2) clear instructions; and

3) a tracking tool to help learners monitor their progress towards the task objective, for example a checklist or rubric.

It’s also important to consider differentiation. Even in classes identified as “single level”, there can be distinct variations in language proficiency. Support learners’ varied needs by having them work in like-ability (same-ability) teams on the same basic task but with adaptations that make the task level-appropriate, e.g. scaffolding for lower-level learners and increasing the challenge for higher-level learners. Another option is to place learners in cross-ability (different-ability) teams, working on the same task but providing task roles that allow each team member to participate fully.

The three task examples included with this blog are categorizing, dictocomp and problem solving. Most textbooks have the raw materials you can use to employ one or more of these task types in your lesson. (E.g. a set of vocabulary from a unit, a listening passage, a conversation, photo or text that poses a problem.) These tasks can be differentiated for the proficiency level of your learners and can help learners develop the skills they need to transition into college, career and community settings. For example, learners in each of these tasks “prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners” (CCR Speaking/Listening Standard 1) and “present information and supporting evidence such that a listener can follow the line of reasoning and organization.” (CCR Speaking/Listening Anchor Standard 4). There are also opportunities for teams to “develop and strengthen their writing by planning, revising, editing, rewriting or trying a new approach” (CCR Writing Anchor Standard 5).

Download the three task examples here.

Developing a task repertoire that includes college and career readiness skill development is relatively painless when you can base your tasks on the practice activities in your textbook.

Are you attending TESOL 2017 this year? Join me on Wednesday 22 March at 10.30am to further explore how we can help our adult learners achieve their personal and profession goals using tasks to integrate the College and Career Readiness Standards in to our lessons. Find out more here.

For more educational resources to use in class visit the Oxford Picture Dictionary Third Edition Teacher’s Club website.

References

American Institutes for Research. (2016) English Language Proficiency Standards for Adult Education. Washington, D.C: AIR

Ellis, R. (2006)” The Methodology of Task-based Learning.” Asian EFL Journal, Volume 8, Number 3. Retrieved on February 1

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1991). “Language learning tasks: Teacher intention and learner interpretation.” ELT Journal, 45, 98-107

Nunan, D. (1987) Designing Tasks for the Communicative Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pimentel, S. (2013) College and Career Standards for Adult Education. Washington, D.C.: Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education.

Prabhu, N.S. (1987) Second Language Pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Willis, D. and Willis, J. (2007) Doing Task Based Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Reblogged this on ELT by M Amin Gental.