OUP offers a suite of English language tests: the Oxford Online Placement test (for adults), the Oxford Young Learners Placement Test, the Oxford Test of English (a proficiency test for adults) and, from April 2020, the Oxford Test of English for Schools. What’s the one thing that unites all these tests (apart from them being brilliant!)? Well, they are all adaptive tests. In this blog, we’ll dip our toes into the topic of adaptive testing, which I explored in more detail in my ELTOC session.

The first standardized tests

Imagine the scene. A test taker walks nervously into the exam room, hands in any forbidden items to the invigilator (e.g. a bag, mobile phone, notepad, etc.) and is escorted to a randomly allocated desk, separated from other desks to prevent copying. The test taker completes a multiple-choice test, anonymised to protect against potential bias from the person marking the test, all under the watchful eyes of the invigilators. Sound familiar? But imagine this isn’t happening today, but over one-and-a-half thousand years ago.

The first recorded standardised tests date back to the year 606. A large-scale, high-stakes exam for the Chinese civil service, it pioneered many of the examination procedures that we take for granted today. And while the system had many features we would shy away from today (the tests were so long that people died while trying to finish them), this approach to standardised testing lasted a millennium until it came to an end in 1905. Coincidentally, that same year the next great innovation in testing was established by French polymath Alfred Binet.

A revolution in testing

Binet was an accomplished academic. His research included investigations into palmistry, the mnemonics of chess players, and experimental psychology. But perhaps his most well-known contribution is the IQ test. The test broke new ground, not only for being the first to attempt to measure intelligence, but also because it was the first ever adaptive test. Adaptive testing was an innovation well ahead of its time, and it was another 100 years before it became widely available. But why? To answer this, we first need to explore how traditional paper-based tests work.

The problem with paper-based tests

We’ve all done paper-based tests: everyone gets the same paper of, say, 100 questions. You then get a score out of 100 depending on how many questions you got right. These tests are known as ‘linear tests’ because everyone answers the same questions in the same order. It’s worth noting that many computer-based tests are actually linear, often being just paper-based tests which have been put onto a computer.

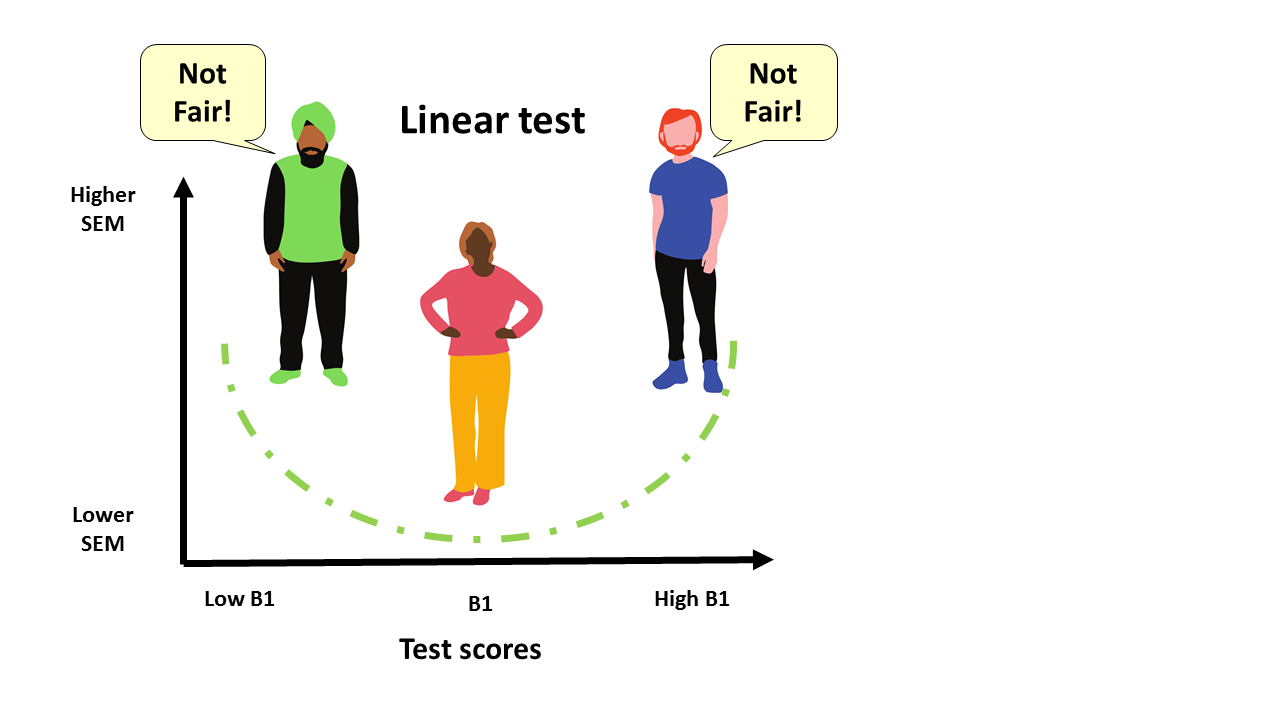

But how are these linear tests constructed? Well, they focus on “maximising internal consistency reliability by selecting items (questions) that are of average difficulty and high discrimination” (Weiss, 2011). Let’s unpack what that means with an illustration. Imagine a CEFR B1 paper-based English language test. Most of the items will be around the ‘middle’ of the B1 level, with fewer questions at either the lower or higher end of the B1 range. While this approach provides precise measurements for test takers in the middle of the B1 range, test takers at the extremes will be asked fewer questions at their level, and therefore receive a less precise score. That’s a very inefficient way to measure, and is a missed opportunity to offer a more accurate picture of the true ability of the test taker.

Standard Error of Measurement

Now we’ll develop this idea further. The concept of Standard Error of Measurement (SEM), from Classical Test Theory, is that whenever we measure a latent trait such as language ability or IQ, the measurement will always consist of some error. To illustrate, imagine giving the same test to the same test taker on two consecutive days (magically erasing their memory of the first test before the second to avoid practice effects). While their ‘True Score’ (i.e. underlying ability) would remain unchanged, the two measurements would almost certainly show some variation. SEM is a statistical measure of that variation. The smaller the variation, the more reliable the test score is likely to be. Now, applying this concept to the paper-based test example in the previous section, what we will see is that SEM will be higher for the test takers at both the lower and higher extremes of the B1 range.

Back to our B1 paper-based test example. In Figure 1, the horizontal axis of the graph shows B1 test scores going from low to high, and the vertical axis shows increasing SEM. The higher the SEM, the less precise the measurement. The dotted line illustrates the SEM. We can see that a test taker in the middle of the B1 range will have a low SEM, which means they are getting a precise score. However, the low and high level B1 test takers’ measurements are less precise.

Aren’t we supposed to treat all test takers the same?

How computer-adaptive tests work

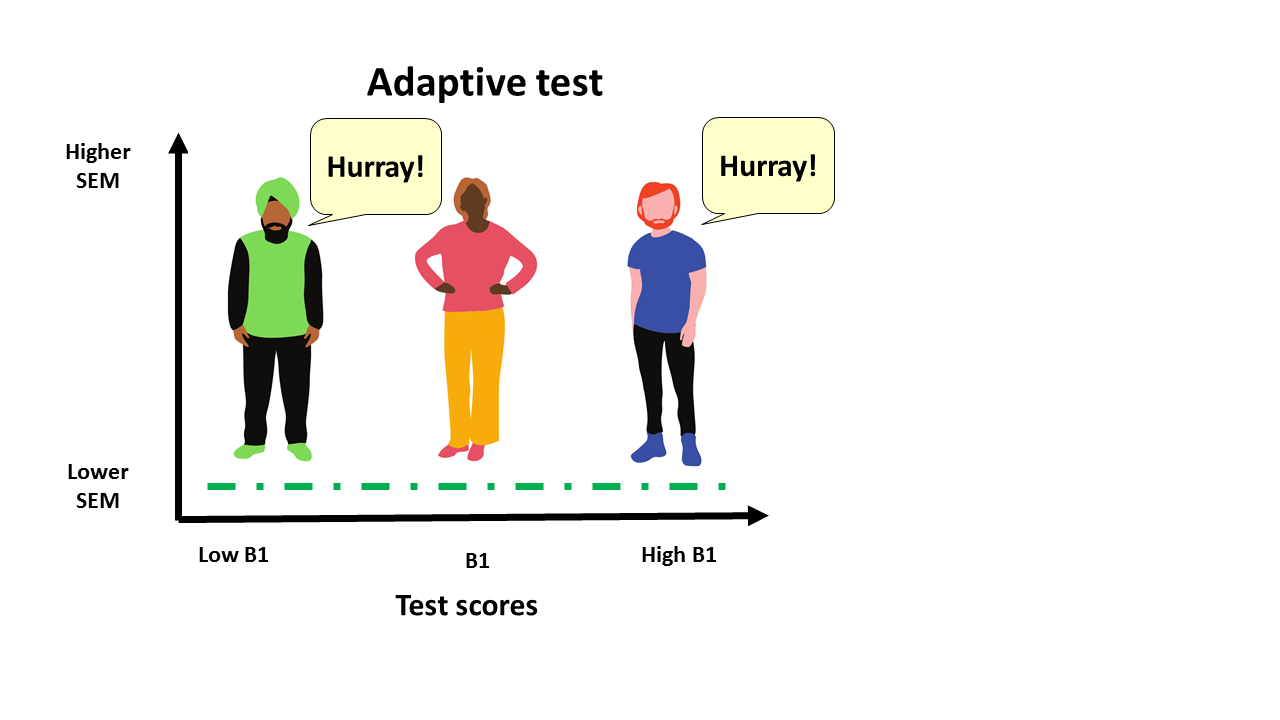

So how are computer-adaptive tests different? Well, unlike linear tests, computer-adaptive tests have a bank of hundreds of questions which have been calibrated with different difficulties. The questions are presented to the test taker based on a sophisticated algorithm, but in simple terms, if the test taker answers the question correctly, they are presented with a more difficult question; if they answer incorrectly, they are presented with a less difficult question. And so it goes until the end of the test when a ‘final ability estimate’ is produced and the test taker is given a final score.

Binet’s adaptive test was paper-based and must have been a nightmare to administer. It could only be administered to one test taker at a time, with an invigilator marking each question as the test taker completed it, then finding and administering each successive question. But the advent of the personal computer means that questions can be marked and administered in real-time, giving the test taker a seamless testing experience, and allowing a limitless number of people to take the test at the same time.

The advantages of adaptive testing

So why bother with adaptive testing? Well, there are lots of benefits compared with paper-based tests (or indeed linear tests on a computer). Firstly, because the questions are just the right level of challenge, the SEM is the same for each test taker, and scores are more precise than traditional linear tests (see Figure 2). This means that each test taker is treated fairly. Another benefit is that, because adaptive tests are more efficient, they can be shorter than traditional paper-based tests. That’s good news for test takers. The precision of measurement also means the questions presented to the test takers are at just the right level of challenge, so test takers won’t be stressed by being asked questions which are too difficult, or bored by being asked questions which are too easy.

This is all good news for test takers, who will benefit from an improved test experience and confidence in their results.

Colin spoke further on this topic at ELTOC 2020. Stay tuned to our Facebook and Twitter pages for more information about upcoming professional development events from Oxford University Press.

You can catch-up on past Professional Development events using our webinar library.

These resources are available via the Oxford Teacher’s Club.

Not a member? Registering is quick and easy to do, and it gives you access to a wealth of teaching resources.

Colin Finnerty is Head of Assessment Production at Oxford University Press. He has worked in language assessment at OUP for eight years, heading a team which created the Oxford Young Learner’s Placement Test and the Oxford Test of English. His interests include learner corpora, learning analytics, and adaptive technology.

References

- Weiss, D. J. (2011). Better Data From Better Measurements Using Computerized Adaptive Testing. Testing Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences Vol.2, no.1, 1-27.

- Oxford Online Placement Test and Oxford Young Learners Placement Test: https://elt.oup.com/feature/global/oxford-online-placement/

- The Oxford Test of English and Oxford Test of English for Schools: www.oxfordtestofenglish.com

[…] Finnerty writes about the importance of providing students with the ‘right level of challenge’ in formal assessment. This is equally important in informal assessment activities, especially in […]

[…] Finnerty writes about the importance of providing students with the ‘right level of challenge’ in formal assessment. This is equally important in informal assessment activities, especially […]